The FWS Judgment, Critiqued - Section 3

What works and what doesn't

Part 8

This is the penultimate part of this analysis, considering the treatment by the Court of the single sex exceptions (remember, not exemptions). This is the most problematic part of the judgment, and the most open to be used against women. But let’s go in order. The Court starts by looking at the separate and single sex exceptions. It is important to remember two things before we look at this part of the judgment.

The Equality Act does not mandate separate and single sex spaces, but only provides a justification for them, so that offering them is not considered a breach of s29 (discrimination) of the Act. In short, the sex exceptions allow service providers to lawfully discriminate between the sexes.

Separate and single sex are two different conditions. In the first, the same service is provided separately for the two sexes (for example, toilets, or changing rooms); in the second, the service is provided only to one of the sexes, because only one has a need for it (for example, screening for female cancers). This distinction is important, though it is hardly if ever noted, because of the consequential effects on people with the PC of gender reassignment and/or a GRC. In the first case, the issue is which of the two services may transsexuals use, the male or female ones, and the easy solution is the offer of a sex neutral option. In the second case, there is a categorical exclusion and the lack of provision of the service completely, if it is recognised that by sex one intends biological sex. It should also be noted the low threshold for the provision of single sex services (that a person “may reasonably object” if the service was open to persons of the other sex). These points seem banal and obvious, but they do have an effect if one is concerned with the resolution of the possible conflict of rights.

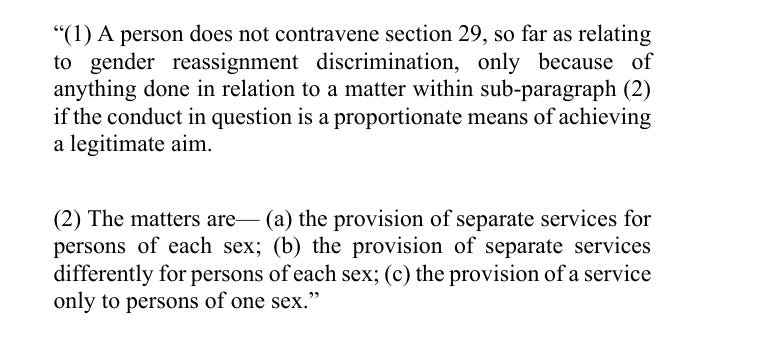

Para 26 of Schedule 3 allows for the provision of separate services for the sexes and para 27 for single sex services. It is quite obvious, as the Court notes, that these exceptions would be rendered nugatory if people could claim, through their GR PC, to belong to the opposite sex, and this would apply for people in possession of a GRC as well. It serves to remind that paras 26 and 27 do not mention the GRA, GRCs or acquired gender, but as we have seen, para 24 of the same schedule does, when dealing with marriage celebrants, so clearly the drafters were aware of when possession, real or presumed, of a GRC would have an effect on the exceptions.

It is also important to remember that GR is a “sex neutral” characteristic, as age, or race, or disability, are. What matters, as rightly noted by Lady Dorrian, is not the sex of the individual, but the reassignment from one sex to the other. There will be circumstances where the sex of the individual is material to the alleged discrimination, so this will affect the comparators. But in the sex “exceptions” there is no need for comparators, because one does not have to prove that unlawful discrimination took place because of a protected characteristic (where, therefore it is important to know whether the protected characteristic is the reason for the discrimination and where, consequently, one needs to find a comparator, real or hypothetic, without that PC); in the sex exceptions, discrimination is lawful sub modo, i.e., if the conditions for the exception are met. But the conditions, which consist in the proportionate means test, are not related to the protected characteristic. The PC is the threshold criterion. So if you are a male you can be excluded, provided the conditions about proportionality are met. There is no need for comparator.

It remains important, however, to remember that sex and gender reassignment are separate characteristic, though they intersect in significant manners. Their intersection has caused the most intractable and problematic point in the judgment, the analysis of para 28 of Schedule 3 (Gender Reassignment). While paras 26 and 27 allow for the discrimination on the basis of sex in the provision of separate and single sex services, para 28 allows for gender reassignment discrimination in the provision of separate and single sex services, so it is linked to paras 26 and 27.

But even before moving to the analysis of para 28, the Court has this to say about the difficulties of interpreting sex as to include “certificated sex” so that a man with a GRC and therefore a female acquired gender has the right to use single and separate sex services reserved for women:

This language is unacceptable. It is not for men to decide whether their presence in a female only space compromises the privacy and dignity of the female users. The Court is still labouring under the misapprehension that being trans is about “passing” (in the eyes of whom?) and this has the most disastrous consequences in para 28.

This is the text of para 28:

I should not first of all the language, which diverges slightly from the language of the other paragraphs, especially that “anything done in relation to a matter” which refers, in fact, to the exceptions covered in the previous paragraphs, i.e. the provision of services for only one sex, for sexes separately, or differently for both sexes. It seems to me clear that this provision is to be read as a “for the avoidance of doubt provision”, and the language bears that out. So, discriminating against a person with the protected characteristic of gender reassignment in the context of the provision of separate or single sex services is lawful discrimination and not a breach of s29. The question remains, how do you discriminate against a person with the PC of GR in providing separate or single sex services? Remember that GR is a sex neutral PC and the definition refers to a transsexual person, not a transsexual male or a transsexual female, or a transsexual man or woman. In fact, if that were the case we would be in doubt whether by transsexual man the EqA refers to a man or a woman. The EqA consistently refers to persons with the PC of GR and, although the pronoun switch in the explanatory notes is confusing, it is reasonably clear a “transwoman” is a male person with the PC of GR, and a “transman” is a female person with the PC of GR ( I use transwoman and transman as these terms are, incorrectly in my opinion, used by the Court). So, to go back to para 28, the language is purposedly generic because it has to cover a male person with the PC of GR and his demand to use a female service and a female person with the PC of GR and her demand to use a male service. The paragraph clarifies, in my opinion, that their exclusion from a service of the opposite sex is allowed, their GR notwithstanding. This is the only interpretation that preserves the integrity of the sex exceptions in all circumstances and, additionally, matches the explanatory notes examples provided to illustrate the functioning and reason of being of para 28:

The example mentions a male to female transsexual wanting to attend a counselling session for female victims of sexual assault. Although s7 is worded generically, the examples have to take into consideration the specific single or separate sex service provided. So a female service can exclude all men, including those who have the PC of GR. A service for male victims of rape can exclude all females, including those with the PC of GR. Of course one could say that their sex is dispositive and allows the exclusion, but this is why I say this is an avoidance of doubt provision.

This interpretation is quite different from the one adopted by the Court, which is contained in paragraph 221:

The Court does quote the example provided in the explanatory notes which I reported above but it departs from the interpretation of para 28 so much that the example can only then be understood as a misinterpretation of the text of the paragraph by the drafters of the explanatory notes. This could very well be possible, but it is left unexplored and unexplained by the Court. The Court is right to say that this paragraph does not allow merely the exclusion of individuals with a GRC from services for their acquired gender, as posited by Lady Dorrian. There is no textual basis for that distinction, but Lady Dorrian is right to point to the function of para 28 is to exclude people from their “acquired sex” service, only the people are those with the PC of GR, not those with a GRC. The title of the paragraph is enough to grasp its proper scope. And the Court is also right to say that the EHRC is wrong to claim that paragraph 28 would be redundant if sex is biological sex, but only because it is an avoidance of doubt provision, as I posit.

Instead the Court claims the paragraph can be used to exclude, as in the example given, women with the PC of GR from female services if they have too masculine an appearance. Conversely, a feminine man with the PC of GR could be excluded under para 28 from a male only service.

It is obvious that this interpretation raises several quite grave issues:

The Court is advocating separating persons with the PC of GR between those who “pass” as the other sex and those who do not, against the plain language of s7, which specifically prohibits this distinction (see its explanatory notes).

The Court does not say which service these masculine women and feminine men are supposed to use, nor who assesses the degree of masculinity or femininity necessary to trigger para 28; in other words, the Court is arguing there should be a case-by-case assessment in the application of the exception, because not all people with the PC of GR will be too masculinised if they are females or too feminised if they are males. Or, they are arguing that any person who is a transsexual, even if they are completely undistinguishable from the other persons of their sex, can be excluded from their own sex service to the extent their transsexual status becomes known to the service provider.

The Court, and, to their shame, all the interveners, avoid the issue of detransitioners. It stands to reason that a woman suffering from the delusion she is a man will not attempt to attend a female only service, but a woman who has detransitioned and come to terms with her female identity may want to, only to find herself excluded, according to the Court, because her previous medical transition has rendered her too masculine for a female space. There is a previous question to be considered, whether a detransitioner is protected under GR (certainly does not match the definition in s7) but certainly they are protected by discrimination by perception, i.e. the perception by others that they are transsexuals, even if they have desisted and come to terms with their birth sex.

In short the Court considers that para 28 allows service providers to exclude lawfully a masculine woman from a female only service which would be unlawful GR discrimination absent the exception provided by para 28. This misinterprets para 28, which makes no reference to perception of GR, but perception of SEX. Women would feel uncomfortable about a “transwoman” attending a female only service not because of their perception he is a transsexual, but because of their perception he is a man. It seems quite patronising to claim that women would not understand that testosterone could have left a woman with a deep voice and a beard. The clarity brought by the avoidance of doubt provision is to the effect that GR does not provide an entry to female only spaces for transsexual males on the basis of their GR, or the other way around. I sincerely hope there is further clarity brought on this provision, and I note with dismay that none of the influential commentators mention this issue, which I have brought to the attention of anyone who cares to listen as soon as the judgment was delivered:

In fact I had provided this suggestion well in advance of the judgment:

As for the Schedule 12 exception for single sex education institution, I read the absence of an exception for GR as further confirmation that the drafters of the EqA never intended GR to also include children, and so an exception was not necessary, because children are not transsexuals, so once again I depart from the Court (at para 228), and from the AA v NHS case from 2023 on which many GC scholars rely to argue children have the PC of GR and so that they can be transsexuals. I have argued against this case and its conclusions most forcefully on social media, especially with Michael Foran, who is adamant s7 covers children as well. I explain my argument, and expose the weaknesses and faulty reasoning of the case, in this thread and will not rehearse it here, except to point out that anyone who argues that s7 includes children clearly does not understand safeguarding. At all.

I should finally note, on the exceptions section by the Court that, in considering the GR exception for sports, the Court follow the approach already taken in para 28:

Clearly, in the case of sport, a “transman” is excluded from female competitions because testosterone is not an allowed substance, and there is no need to resort to the EqA. But a “transwoman” may be excluded from female sports as a male with the female acquired gender, so once again, an avoidance of doubt provision. In fact, all the debate about sports is about transwomen precisely because females who take testosterone are excluded on the basis of doping rules, not transsexual status. For example, this is the list of prohibited substances from the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA):

In conclusion, while of course I agree with the interpretation of sex as biological sex, I cannot agree with the interpretation that the Court does of gender reassignment exceptions, and this is inevitable, because the Court failed to interpret properly gender reassignment and test the limits of its effect. I argued elsewhere that there are no legitimate limits to this category, which needs to be removed from the EqA altogether. This judgment confirms that I am correct in positing that it is impossible to apply this PC properly, including finding an appropriate comparator. The Court is reduced to claim that masculine women do not belong in the female sex. Surely this cannot be the proper interpretation of the law.

Part 9

I am not overly interested in the misinterpretation by the EHRC of “certificated sex” and the problems it raises. The Commission has shown it is not fit for purpose by misrepresenting the law, failing to protect women and girls and in an all around failure to do its job. Even at this late stage, they failed to acknowledge that their interpretation of the EqA was vitiated by an incestuous relationship with Stonewall. In August 2020 the EHRC paid £3,000 to Stonewall Equality Ltd, for example.

The same money was paid in 2018.

In 2019, they did this. Do I need to tell you how pernicious the influence of Stonewall has been in the NHS? How many women suffered indignities, including exposure, forced nudity, inappropriate touching, because of this collaboration between the NHS, Stonewall and the EHRC? Is an apology coming?

In 2018, they were proud to commend the work of organisations such as Stonewall and LGBT Youth Scotland to spread gender identity ideology in schools. That worked out really well.

LGBT Youth Scotland was led by notorious paedophile James Rennie in 2003. I read the court transcripts of his trial, and I will bring what I have read to my own grave. This organisation should have been disbanded forever. In 2022 two men accused the charity of having abused them and they asked why there was never an inquiry on Rennie, who was convicted of raping a three-month-old baby (you read that right). In 2025, they were berated for advising trans youth to use clean razors for self-harm. The year before, the chair of Children in Need was forced to resign for a grant she had given to LGBT Youth Scotland. This is the organisation the EHRC was associating with from the time when gender identity ideology was allowed to capture all major institutions, institutions over which the EHRC was supposed to keep a watchful eye to make sure they upheld their equality and human rights obligations. Remember that this is their remit and their legal duty:

This is really a case of Quis custodied ipsos custodes (who will guard the guards themselves?). So you will forgive me if I do not care one bit what the EHRCsaid and I reckon there should be an inquiry in their dereliction of duty and the consequences for women and girls.

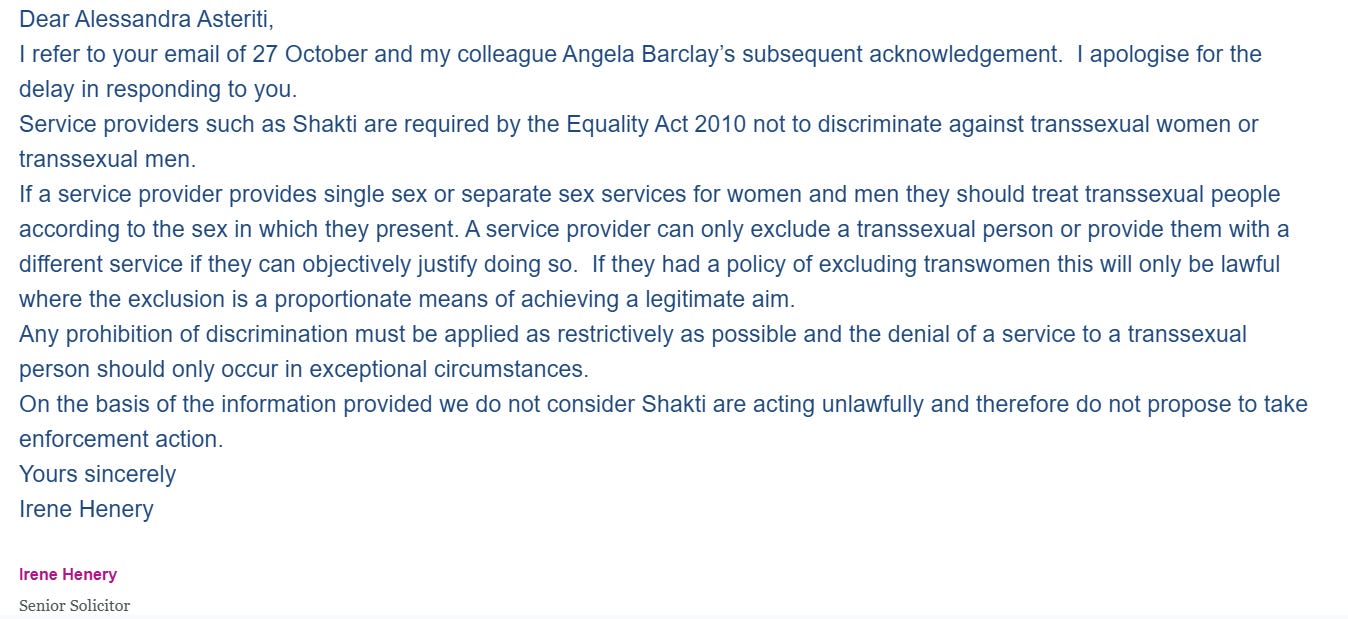

My own interactions with the EHRC are revealing, and of course I have written a thread on them, to show the extent of capture. In 2019, I became concern about Edinburgh charity Shakti Women’s Aid allowing males to self—ID into their refuges. I contacted the EHRC. This is the reply I got from them, from one of their senior solicitors, no less.

As you can see, she is misrepresenting the law, as the Court has just clarified. She should not draw a senior solicitor’s salary from the EHRC to get the law wrong. I had written this to them (notice the date, I gave them a 6 years advance notice on the law).

Again I am not impressed by the EHRC claiming the meaning of sex needs an amendment (espousing the losing Sex Matters’ strategy).

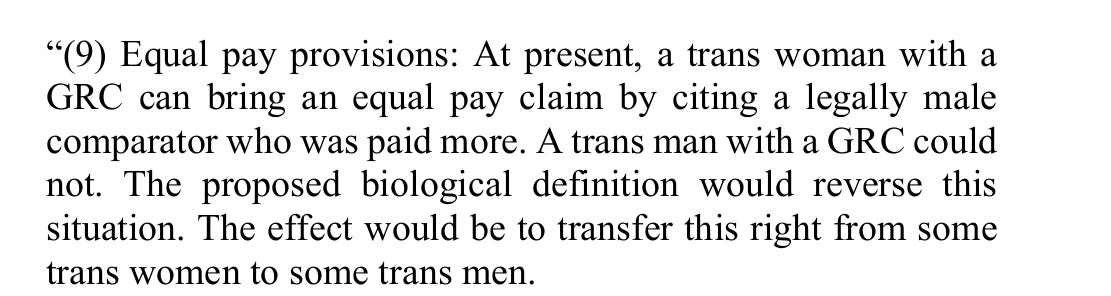

This is what the EHRC is arguing could be a disadvantage of clarifying that sex means only biological sex in the EqA:

They are simply getting the comparator wrong and the law wrong. The PC in the EqA is GR, not possession of a GRC, and the correct comparator is a person without the PC of GR, of either sex. If a woman with the PC of GR is paid less than a woman without that PC, or a man without that PC, she has a claim. Their sex is irrelevant.

To their credit, the Court does not believe that an interpretation of sex as referring to biological sex will affect transsexual people (of course the Court does not use the correct legal terminology, rolling eyes emoji) basically arguing that they are protected against direct and indirect discrimination by discrimination by perception or associative discrimination. I have made this argument repeatedly in the past so it is not novel to me, and it is relatively appropriate as long as GR is not removed from the EqA. This is the gist of the argument:

Of course we all know transsexual males are never perceived as women, except by ideologists who espouse gender identity ideology, and therein lies the problem with this paragraph. It is not advisable to introduce in the law the misconception that males are commonly mistaken for women (this reminds me of the video of the “transwoman” who went out at night all dressed up and then reported that a lot of men yell “f*ggot” to women who are out alone at night) and discriminated on that basis. That is fanciful, though men seem very easily fooled by feminine dress, make-up and fake breasts into believing someone is a woman. To my knowledge, but happy to stand corrected, there are no cases of transsexual males claiming discrimination, harassment or victimisation on the basis of sex, because they were mistaken for women. It just simply does not happen.

I feel I should provide some sort of conclusions, but the issues I have with the judgment have been explored already and do not need restating. The political fall-out of the judgment is a separate issue altogether, which does not belong in this analysis. The threat of an application to the ECtHR seems legally illiterate, but I do know that the capture of the CoE is so complete, that nothing would surprise me. Be warned.