The FWS Judgment, Critiqued

What works and what doesn't

Part 1

You certainly did not expect me to write a paean to the FWS Judgment, did you? I do not consider myself an activist, only a legal scholar trying to make sense of the abyss in which the rule of law has fallen since the trans turn in human rights law, where a smattering of activists, lawyers and judges decided that the law should uphold delusions. Seen from this perspective, the Judgment contains many problematic procedural and substantive issues. This is not to take away from the resounding victory of the Appellants and the welcome clarity which many of us had been pointing out for years, being told, it is complicated, it is contested, it is nuanced. No, it bloody is not. Legally it is crystal clear (and I see now I should have copyrighted this phrase). Equally I do not expect the Judges to come out in favour of repeal of the GRA, regardless of the untenable position, with respect to the rule of law, the GRA puts them in the exercise of their functions.

But first things first. The language. Language is always crucial in law, but never more so in this case, where the entirety of the issue is about the meaning of a small number of words (“man”, “woman”, “sex”, and here you already feel you have entered a dystopia, these being some of the most easily intelligible and uncontested words in the English language, but as the Brits are fond of saying, we are where we are). The Judgment opens with a small section on terminology, where the Court sets out how certain words will be used in the Judgment. I foresee a first problem, legally, with the refusal of the Court to use the term “transsexual”, as done in the EqA, to describe people with the PC of GR. Instead, from the beginning, we find non-legal, activist language such as “members of the trans community” (paragraph 1), defined as an “historically and currently a vulnerable community” (ibidem); women are women, transsexuals are an historically and currently vulnerable community. What, more than women, historically? It is not the task of the Court to give us these tidbits of fake history lessons. I say Judges have a duty to stick to the law as it is, not as Stonewall (the most vocal critic of the “transsexual” language) would like it to be.

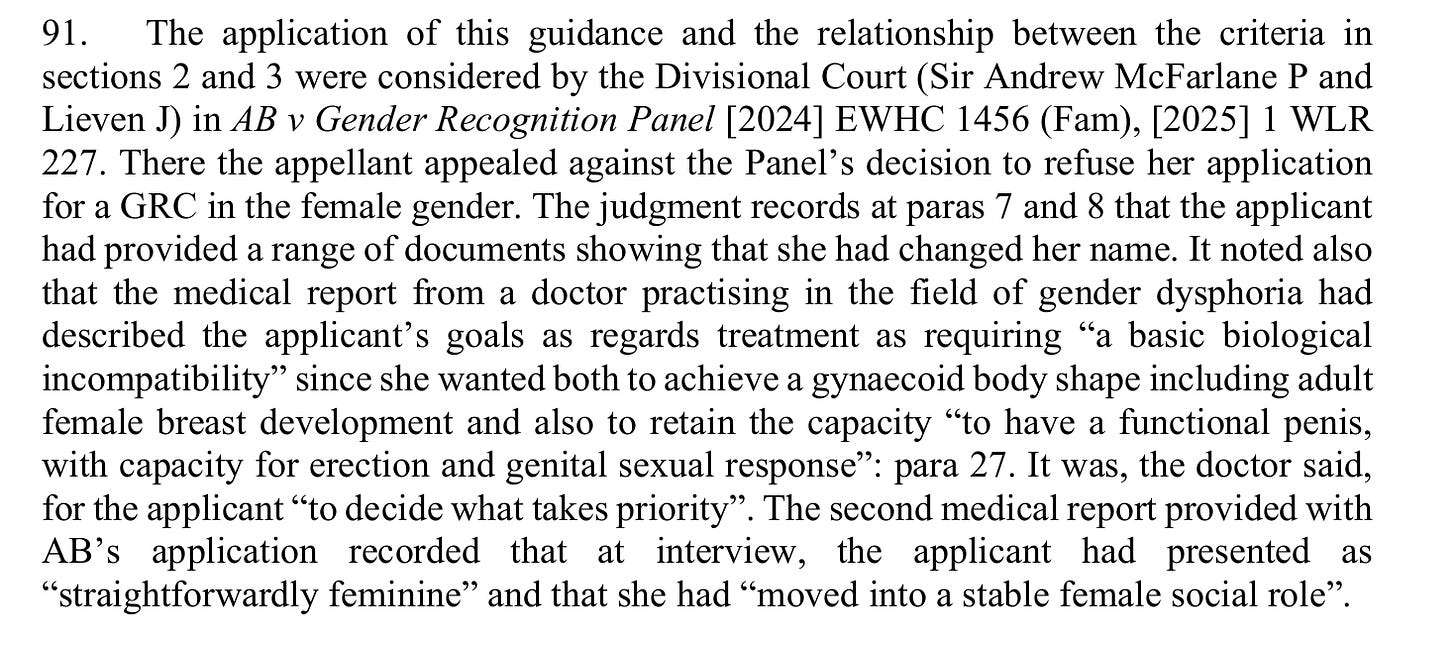

They use trans woman for a man who identifies as a woman and trans man for a woman who identifies as a man. Wrong in law, but of such common use as to be almost uncontroversial. Almost. They do not explain why they use female pronouns for transsexual males and male pronouns for transsexual females, engendering often semantic confusion, for no apparent reason. I feel sorry for Judges who find themselves quoting things like “his womb” (paragraph 106), or talking about a case in these terms:

It should be noted that the Judges argue that this man ought to have been given a GRC, because wanting to be a walking trans porn obsessed male is a female social role. Is it now? Of course the Judges do not mention porn, but agree that this individual should have been given a GRC because he respected the criteria for conferral. If a man who wants to retain a functional penis while having fake tits and cross-dressing is respecting the GRA, then the GRA is an absurd law.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Paragraph 91 actually caused me to develop a bout of nausea at the thought of this pervert and more, at the perversion of the law and the judicial process involved in allowing him to successfully judicially review the refusal to grant him a GRC. If I think of the major injustices that go unaddressed because the victims do not have the money or the circumstances for accessing a judicial review, including all the women and girls victims of unlawful trans policies, and then I consider this case, it is hard not to move into activist mode. It is also hard to understand why the UKSC decided to go into such detail on this case, which surely would turn off even those of us with the strongest stomachs, if not for reasserting that the “live in the acquired gender” criterion is strictly procedural and only refers to things such as documents and pronouns. The logical and legal difficulty with such an approach deserves its own treatment.

To go back to the case, this is a case about statutory interpretation, not human rights, as many said disagreeing with me, and no, it is not “extremely complex” as some said; it is in fact remarkably straightforward, and the Court could have made several more arguments to prove its point, and I imagine it did not do so for reasons of judicial economy. There is one argument that I wish would have been made, because it points to a basic rule of statutory interpretation. The Court says that it will consider the meaning of words such as “man”, “woman”, “male”, “female” and “sex” (paragraph 8). In fact, the Judgment does not consider in detail the meaning of “male” and “female” and this is a pity, because one of the best arguments that “man” and “woman” have their biological meaning only is that they are defined in s212 with reference to being male and female respectively. No reasonably drafted statute defines a word with reference to another word that is in itself contested and possesses multiple meanings. Male and female refer solely and exclusively to our sexed nature as mammals, and mirror the words as used to refer to millions of animal and plant species. So the fact that man and woman are defined with reference to male and female is dispositive of the appeal already.

I am following the Judgment as it goes. Next, the Court states that this Judgment is about statutory interpretation and quotes as authority, R (O) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2022] UKSC 3; [2023] AC 255. This passage is especially important:

This is the closest the Court comes to acknowledging the main issue with the disruption the “trans turn” provoked in the law, i.e, decoupling law from reality and making it unintelligible to the individuals subject to the law. As the perusal of this Judgment will draw out, the corruption of language brought about by this trans turn is so complete that the Judges themselves submit to the rules of this ideology without a moment’s concern for the reliability of the law and the reliance the law’s subjects ought to be able to have towards its rules, duties and rights. What trust can one put in a caselaw that talks about women having erections (paragraph 91)? I will mention the most egregious examples of this corruption of language and logic, which cannot be remedied by a Judgment that maintains the primacy of “biological” sex within the narrow confines of the question posed by the appellants. The Court quotes approvingly from Lord Hodge about the need for citizens to understand parliamentary enactments, while deciding on one such enactment, the Gender Recognition Act 2004, where the most crucial word of the entire act, gender, is never explained, defined or circumscribed. What are citizens supposed to make of this word, and how their advisers helping them in their understanding?

Part 2

Before I continue the textual analysis, one more general point, which will reverberate throughout the analysis. When you investigate the meaning of a word in relation to another word, you necessarily have to engage with the meaning of both. To explain, if the question had been, “does widget mean sex?” clearly one would have expected at some point an analysis of the word widget. Instead, we have an entire 88 pages judgment about the relationship between gender recognition and sex without any discussion on the meaning of gender. What exactly gets recognised, and in the EqA, reassigned? By the end of the judgment, we are none the wiser.

This brings us quite neatly to paragraph 10 and the discussion on the contextual interpretation rule, that is, that a word needs to be interpreted in the context of the Act where it appears. More precisely, contextual interpretation has several layers. The first one, a word needs to be interpreted in the context of the Act. The extension of the contextualisation is directly proportional to the contested or “controversial” nature of the word. So the context can be extended to incorporate the historical context of the situation that brought Parliament to legislate on the matter and further, logically, the context can then extend to the parliamentary debates and other legislative sources. Crucially, the interpretation has to be extended to these contexts only if the meaning remains ambiguous once the word is considered in the context of the Act only.

The Court equally considers that there is a presumption that one word will have the same stable and coherent meaning throughout the Act, unless this is expressly derogated by a special meaning attributed to the same word in one specific part of the Act. Now this does not happen for the word sex, and I am not spoiling the ending by anticipating that the Court found that the same stable, uncontroversial and common meaning of the word sex, that is the biological differentiation between males and females, applies through the EqA.

Unhelpfully, this leaves the small matter of the meaning of sex in s7 (Gender Reassignment) of the EqA, which so recites:

What does sex mean in this section, and how do you reassign it? The section makes reference to physiological or other attributes of sex. If sex means biological sex, as it does in the rest of the EqA (and as we shall see in the last part, that is how the Court is reduced to interpret it), then at the end of the process, one’s biological sex changes from male to female or viceversa. This interpretation not only goes against everything that is said in the judgment with regards to the applicability of the provisions of the EqA when sex is mentioned, but makes it impossible to apply this meaning without distinguishing between pre-op and post-op transsexuals (the first group remaining of their sex at birth, legally, the second having their sex reassigned, which is not the same as their acquired gender recognised). Quite clearly this cannot be the applicable interpretation. In the absence of an expressed indication in the text, we are forced to extend the context of this provision to include the historical context and possibly the content of the legislative debates about this provision).

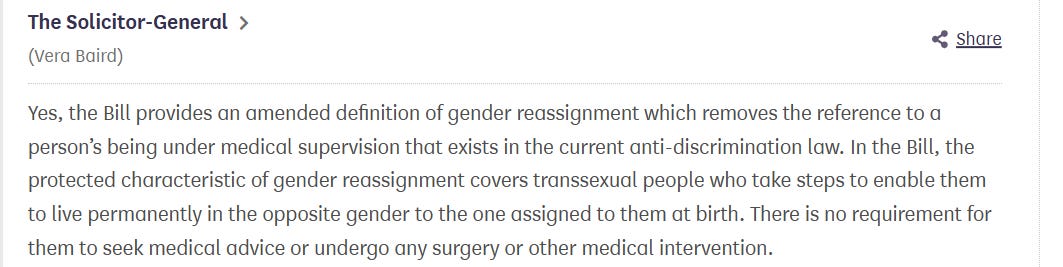

The first thing we ought to notice is that in the parliamentary debates it is clear that the section on gender reassignment was amended to eliminate all references to the necessity of medical supervision or intervention to fall within the protected category:

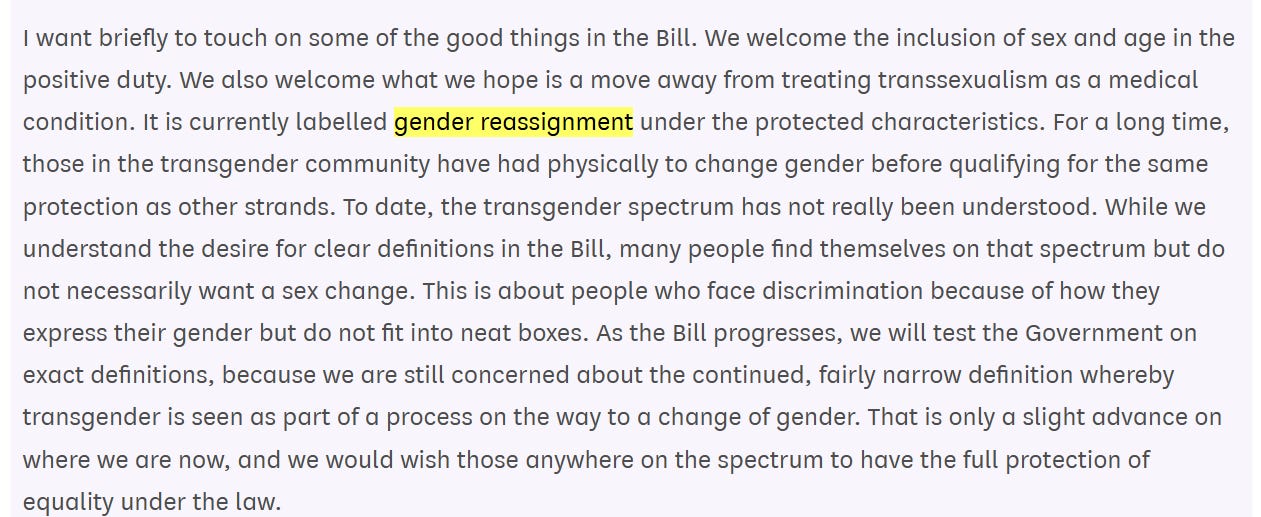

This still does not clarify what is meant by sex in the context of what will become s7. This short exchange is enough to clarify that gender reassignment (sic) is not considered necessary, though again, there seems to be lack of clarity between gender and sex, nor are the “other attributes” of sex clarified. Does this mean one’s attire? But clothing is not an attribute of sex. The only clothing that is really sex specific tends to be underwear, which is not normally visible. All the same, a Hansard search of the terms “other attributes of sex” reveals that in parliamentary debates these are taken to refer to “name, clothing or hair” (I have remarked several times how gender is nothing but stereotypes and this seems to be an official confirmation of that.)

This explanation from Lynne Featherstone, LibDem MP is beyond unhelpful, with muddled language on “transgender spectrum” and sex and gender used indiscriminately:

A search in the case law of the Supreme Court on the terms “other attributes of sex” only brings out the judgment under analysis here. I did not engage in any further research. But the point is, why didn’t the Court? What does sex mean in s7? Biological sex? I envision problems with this, as I have outlined already here, and probably more. So this is one of the first examples of the issues arising from the refusal to engage in a proper linguistic analysis of the two terms. One cannot clarify completely what sex is taken to mean in the EqA if one does not clarify was gender is taken to mean in the EqA, as evident in s7.

Part 3

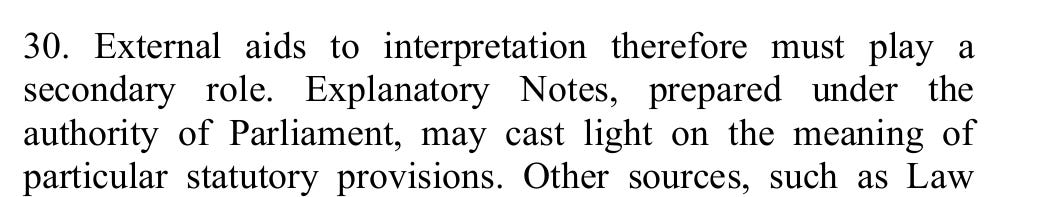

I pick up where I left off, with the lengthy quote from Lord Hodge, just to flag the issue of Explanatory Notes, which will be relevant later. This is what he says:

Remember this, because one of the most contentious provisions in the EqA, para 28 of Schedule 3, was interpreted by the Court in a manner inconsistent with the example given in the Notes, and the Court does not even mention this. One would have expected more transparency on this particularly contentious issue, which will be dealt with in due course.

In this regard I should also note that the Court stresses strongly that this case is better dealt with as a matter of statutory interpretation, focussing on the contextual and consistent meaning of words through statutes. So sex retains throughout the EqA its meaning as a biological class. There are two aporias in its approach: first, the Court insists in defining sex without any reference to gender, though the issue at hand is whether the GRC expands the sex classes to include those who have a gender recognition certificate, so it seems logical to assume the Court would have an interest in defining this word (which, as we know, lacks both a legal definition and a common dictionary meaning); second, the Court insists that sex means biological sex in all the EqA, but this would include s7, as we have already seen. But also, importantly, gender is used inconsistently in the EqA, both as part of the PC of gender reassignment, and in s78, in the phrase “gender pay gap” where it presumably refers to the use of gender as a synonym of sex (in fact the section talks about male and female employees). It may very well be that the meaning of gender is beyond the scope of the appeal (the main reason why I was not convinced it was the correct legal strategy to ask the court to clarify what was already crystal clear, leaving unclarified what was not clear at all), but there is a theoretical problem with clarifying the meaning of sex only. Theoretically, clarifying that sex means biological sex does not preclude the law developing in the direction of recognising that gender can also mean biological sex (in fact it is one of its several meanings) and further, that gender reassignment can then mean (biological) sex reassignment. And the history of the last 30 years has taught me not to trust any open ended interpretation of these terms. Gender needs a definition that takes into account its several uses (gender as per Istanbul Convention, gender as synonymous of biological sex, gender as what gets reassigned, the most contentious of them).

I have said, more times than I care to remember, that the issue of the relationship between the material reality of sex and the belief in gender identities is an issue capable of raising rule of law concerns, for several reasons. First, the law should not reify beliefs and attach positive rights to them; second the law should not force people to break the law (for example, the Workplace Regulations, which establish a clear duty to provide separate sex toilets and changing rooms) by forcing them to follow gender identity beliefs instead, as reified in the law; and third, the law needs to be easily intelligible to every citizen, a point that is also made by the Court:

So it is ironic that the court does not concern itself with statutes, such as the GRA and the EqA, which do not provide any definition of gender while establishing duties around its reassignment or recognition. What exactly is getting reassigned, and what is the State recognising? Don’t we all deserve to know? Do not take this as a political point. It goes to the heart of the rule of law, the most majestic contribution of English law to the world. Legality, legal certainty, lack of arbitrariness, equality before the law. None of this survives the perversion of reality inherent to creation of the “female penis”.

This is how the Court frames the question at the centre of this case:

There is no indication that sex and acquired gender mean the same thing. On any reasonable reading of the GRA, informed, amongst other things, by the duty to interpret legislation so as to comply with the UK’s international human rights obligations, including the obligation to protect women against “sex based” discrimination (Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women), the GRA does not modify the meaning of sex. Indeed, if sex did not retain a stable and consistent meaning, it would be impossible to allow acquired gender to sometimes be read as sex. Incidentally, the only reason why sex is mentioned in s9 GRA is because birth certificates only contain information about sex. Basically, the GRA allows to read one’s acquired gender in place of sex when birth certificates are used as a way to ascertain sex. Any talk of “legal sex” or “certificated sex” as referred to by the Court is contrary to the plain language of the GRA and ignores two crucial points: first, birth sex as recorded in the Register of Births is never changed, so people with a GRC retain their sex at birth; second, we all have a legal or certificated sex. What makes me and a person with a GRC different is precisely that they have a GRC, which modifies their birth certificate, and I do not. Our sex never changes.

The Court needs to consider how Lady Haldane and Lady Dorrian dealt with the appellant’s challenge, first in the Outer than in the Inner House of the Court of Session. I will waste no time on the judgment by Lady Haldane. Lady Dorrian in the Inner House argued as follows:

With respect (and with fond memory of my personal interactions with her) I think Lady Dorrian here fails to properly distinguish between a simple non-discrimination provision, which may indeed equally protect women and men with the PC of GR, if nothing else because of discrimination by perception (as the court itself concludes later, and as I have argued repeatedly in the past), and positive rights granted to women, such as the possibility to be granted specific single sex services on the basis to the sex exceptions, whereby discrimination is not only not unlawful, but expressly permitted by the EqA. Negative and positive rights, and the corresponding duties, are not the same thing. There is no necessary connection between the claim that a transsexual male may claim sex based discrimination on the basis of discrimination by perception, and the demand that a transsexual male is thereby allowed to use a female space, or be given a place on a board to increase the number of females on that board.

To repeat an example I have used in the past, when I lived in Germany I was often mistaken for a Syrian refugee, and sometimes treated with contempt in public. This could have given rise to a claim of discrimination on the basis of race, or ethnic origin, if it had happened in a situation covered by the EqA and it had happened in the UK. But it would not have allowed me to claim State support as a refugee. So the fact that a transwoman can claim discrimination is neither here or there when determining if he is in fact a woman (spoiler, he is not).

And on this note (receipts are my obsession), I end this part.

Part 4

Part 6 of the Judgment is about the legal background to the Equality Act, starting with the Sex Discrimination Act of 1975 and following with the 1999 Regulations which inserted gender reassignment into the SDA. This is clearly where the rot starts, as gender is not defined and we are quite aware, as I evidenced in my book, of the cultural background in which this legislation took form, included the cultural stereotypes associated with transsexuals, as evidenced in the case law. The Court is quite happy to use gender as a synonymous of birth sex, hence biological sex, begging the question about what exactly gets reassigned, with or without surgery. This can result in unhelpful ambiguities, such as, when describing the P v S and Cornwall County Council case in the then ECJ in 1996, the Court refers to the applicant as a biological male who was discriminated on the ground of “her” sex because he was dismissed when he announced his intention to undergo plastic surgery to mutilate his genitals (I use descriptive, not ideological, terms). The acceptance, on the part of the ECJ that discrimination on this basis is a form of sex discrimination, hence covered by the Equality Directive, represents the trans turn in equality law just as Goodwin represents the trans turn in human rights law. The case, as summarised by the Court, is a series of non sequiturs, hanging fundamental principles on an undefined concept, gender reassignment, describing a material impossibility, changing sex.

The Court summarises the GRA’s history, and one is once again struck by the ridiculousness of the argument underpinning the ECtHR’s decision in Goodwin. The Court is not precise in its summary, as the GRA does not recognises gender reassignment, but acquired gender (both are meaningless terms in themselves, of course, but the first one presumes surgery, and the second one does not, and in fact the GRA dispenses with the need to have surgery, which was the entire basis of the ECtHR’s reasoning in Goodwin).

I have written many times about how badly drafted the GRA is and how hapless courts have been in interpreting it. I was expecting a little better from the Supreme Court then to repeat the guff about “living in the other gender” as if this were a possibility. In fact the argument that this can be evidenced by things such as change of name and utility bills betrays a basic misapprehension. Making other people treat you as if you were the opposite sex has nothing to do with “living” as the opposite sex. The onus is strictly on third parties and yet, this is the only evidence that has a semblance of legality and legitimacy, otherwise one would have to look at things such as dress, speech and mannerisms, as listed in the Yogyakarta definition of gender identity. The Court deals with the “living in the acquired gender” requirement at paras 87 ff., and quotes the sort of evidence one must present as proof:

It is clear that none of these actions (changing name, imposing the use of certain pronouns to other people, changing documents) require any change in one’s life, but only impose duties on third parties and at most, a simple bureaucratic change from the affected person. Lady Hale waxes lyrical about transwomen who undergo feminisation surgery, but the reality is that these are neither required nor common.

At para 91 the Court report this story. I am copying it in its entirety to evidence the sort of case law emerging from the GRA.

As a legal scholar I really struggle to understand how judges can pervert reality to such an extent and maintain the pretence that they are applying the law. A perverted man who wants to perform a porn soaked fantasy about having breasts and a functional penis is described as having moved into a stable female social role. The Court concludes that this man (whom the Court refers throughout as a woman) should have been granted a GRC.

In summarising the effects of s9(1) of the GRA the Court (or the Scottish Government, whose submissions the Court is quoting) commits a serious inaccuracy. This is what the Court says:

But this is what the Explanatory Notes for s9 say:

As you can see, the Court refers to a “trans man” but the Notes to a “trans woman”. So the comment of the Court on the limited value of Notes is misplaced, especially as the Court is generalising on the value of the Notes on the basis of a mistaken reading of them. One wonders whether everyone is just getting confused by the idiocy of calling some men women and some women men, and still pretending to make sense of things. It is indeed exhausting to keep track of pronouns changing mid-sentence and men being called women. [Addendum: the court has now corrected this paragraph, to match the language of the Notes.]

This section of the judgment suffers from repeated references to the case law originating from Lady Hale, remarkable for its lack of clarity and its “be kind” attitude, always inimical to good law. This is a classic example, as quoted by the Court:

There is nothing I can say to save this Stonewall-lite jargon, and would hope to see it consigned to history soon. Not even trans rights organisations talk about being born in the wrong body (the wrong genitalia, actually) so this judgment is really of its time.

The Court next considers the case law on the effect of from s9(1). I have stated my position on this repeatedly in the past, and I can summarise it as follows:

“all purpose” refers to all legal purposes, as confirmed by Judge Choudhury in the EAT in Forstater v CGD.

Additionally, the condition has to be further reduced for “all legal purposes in which sex is ascertained by birth certificate” since that is the legal way in which acquired gender has an effect, that is, to allow for a change in the birth certificate, where sex at birth is amended (incidentally, this is the only reason why sex is mentioned, and it is mentioned for this meaning only in s9, and that is because birth certificates do not contain gender information).

S22 (Prohibition on Disclosure of Information) reinforces this reading down of s9, as it clarifies that this information is privy only to people who have acquired it in an official capacity (and possibly, family and friends, but private sharing of this information is not the concern of the GRA).

Even if this interpretation was not sufficiently clear from the plain text of the Act, courts have a duty to try to interpret it, if possible, in a way compatible with the HRA 1998, including taking into consideration the rights of third parties and specifically, of women. If such an interpretation is not possible, they should actually issue a declaration of incompatibility, as per s4 HRA. They have never done so.

All of this I have written about well in advance of this judgment. I should add that I expressed my doubts that s9 was a “deeming provision” in the way this term is commonly used in law, as it has a very specific and technical meaning. In this I was basically a minority of one, with all the GC legal scholars and practitioners commonly referring to s9 as a deeming provision. I will not rehash my arguments against the use of this term, but here is a thread about it. The Court is quite curt about the use of this term, which has now been wiped out from all the commentary on this case, starting with Foran, who was most insistent on using it before 16 April.

The fact that the Court says it is useful as an analogy does not mean it is implicitly saying s9 is a deeming provision. It seems to me some people thought deeming provision was a nice euphemism for legal fiction (as gender is for sex) and adopted it enthusiastically, without considering the finer distinctions between the general concept of a legal fiction and the specific and technical meaning of deeming provision.

The Court says that sex and gender are used interchangeably in s9 and I do not think this is precise enough. As I said, I think s9 HAD TO mention sex, as sex is the terminology of the birth certificate, so it had to say that the acquired gender replaces sex. The terms are not interchangeable, as I said countless times, because, while you can use gender as a euphemism for sex, you cannot use sex to replace gender and in fact, all the problems we currently have in interpretation arise for the facile conclusion that the two terms are interchangeable.

Paras 99-100 are of crucial importance and, I would argue, an unwelcome crossing of the boundary between judiciary and legislature by the Court.

With respect, it is not for the Court to determine which legislation is relevant, but only to apply legislation as it comes from Parliament. Also the imprecise language betrays a certain level of ideological fuzziness (I am not talking here of ideological capture, but of lack of precision in the language). The GRA is not about “transgender people" and their “rights”. It is not about autonomy and dignity and tell us nothing about discordance between their sense of identity and their “living in the acquired gender” unless seeing a male name on an electricity bill printed by an anonymous computer would engender a loss of dignity in a man who thinks he is a woman. GRCs are so crucial to their dignity and autonomy that only a negligible number of people who call themselves transgender even bothers to get one, and this is the strongest indication of their limited value for the very “community” they are supposed to provide with dignity and autonomy.

It is true that GRCs also concern relationships between private parties, as employers are private parties and they will be aware of GRCs. But their limited value, again, on a proper reading of the GRA, is abundantly clear. This is a very political statement from the Court, and most unwelcome.

I will stop here, before getting on the issue of s9(3).

Thank you, Alessandra. I had been waiting to see what you would say. They could have done it even better, true, and more clearly, but it is a great victory none-the-less. I liked this new (?) expression, "certificated sex". It seems to suggest (more clearly than "acquired gender" or other misleading expressions such as "legal sex") sex according to paperwork, and not the real sex. I think you were suggesting a while ago that "gender identity" could be subsumed under "belief", and thus be protected under "philosophical and religious belief", rather than being a distinct protected characteristic (gender reassignment). Then one would be free to believe that the earth is flat, that men can become women, that 2 + 2 is sometimes 5, and any number of strange ideas, as long as they did not impose them on everyone else. I thought this was a great idea. Though when, I wonder, will we see the belief that sex is binary and immutable protected in some other way rather than as a "philosophical belief", apparently on a par with these above? Still a long way to go...

Alessandra, I am considering the opening statement of our repeal of the GRA to be "We are seeking the repeal of the GRA to re-establish the primacy of Sex: binary (male or female) and immutable over a perceived Gender Identity that differs from one's sex observed in utero and/or at birth and recorded".

P100 of the SC ruling suggests that the GRA grants more than the falsification of sex on documents such as birth certificate, marriage certificate, civil partnership certificate and death certificate (and those only applicable to those who have been issued a GRC by the Gender Recognition Panel).

If the GRA is repealed and the PC of Gender Reassignment subsumed into the PCs of Religion or Belief (that one has a Gender Identity at variance with ones's sex) and Disability (suffering from the contested symptom, not diagnosis, of Gender Dysphoria and the delusion they are not the sex they were born) what rights do you think the SC were thinking of that TW/TIM would be deprived of?