Of Myths and Misconceptions

What does international law really do?

It is an often repeated quip that international law is not law because there are few and weak enforcement mechanisms. You would not know this following the debate on Goodwin and its effects, and on the feasibility of repealing the GRA.

So here are a few myths busted. You may still disagree the GRA ought to be repealed, or think it will be too difficult to do it. But do not hide behind international law, because it will give you no cover.

The Court in Goodwin ordered the UK to pass a law for transgender people.

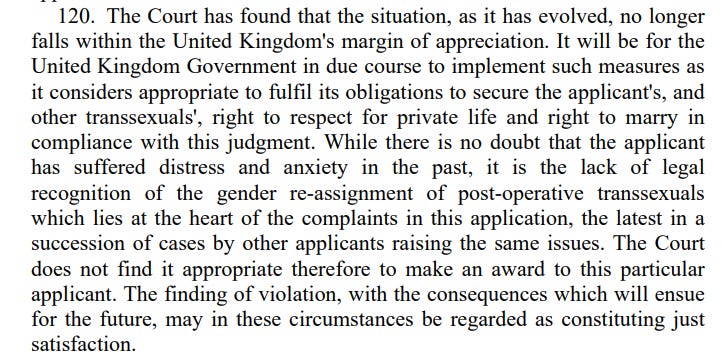

The Court could not have possibly done that, because the ECtHR does not have the power to impose this sort of remedy. According to the Convention, the Court can impose pecuniary damages on a State found to have violated one of the human rights covered by the Convention. There are several hurdles an individual has to go through in order for their application to be declared admissible and for a case to be heard. If the individual is successful, the Court will declare the State party to the proceedings to compensate the individual for the violation of their right. In the case of Goodwin there were no damages and the Court opined that just satisfaction may involve a change in legislation. But this is a change that the Court is not in the power to impose to the UK. All it can note is that the country may be found to have violated an individual’s rights if similar conditions were to obtain. It is within the sovereign power of the country whether it is willing to incur the cost of repeated violations.

Repealing the GRA will create immediately a breach of the Convention and/or force the UK to leave the Council of Europe.

As noted, the Court cannot tell a country which legislation to pass or repeal. It can only accept an application, once domestic remedies have been exhausted, detailing how a specific law or policy or act by a State constitute a breach of a right in the Convention. Speculative applications about how a repeal may constitute a violation of the Convention will be rejected, as well as applications that are not presented by a victim (and this has to be a natural person; legal persons only have rights under Article 1 of Protocol 1, protecting property rights).

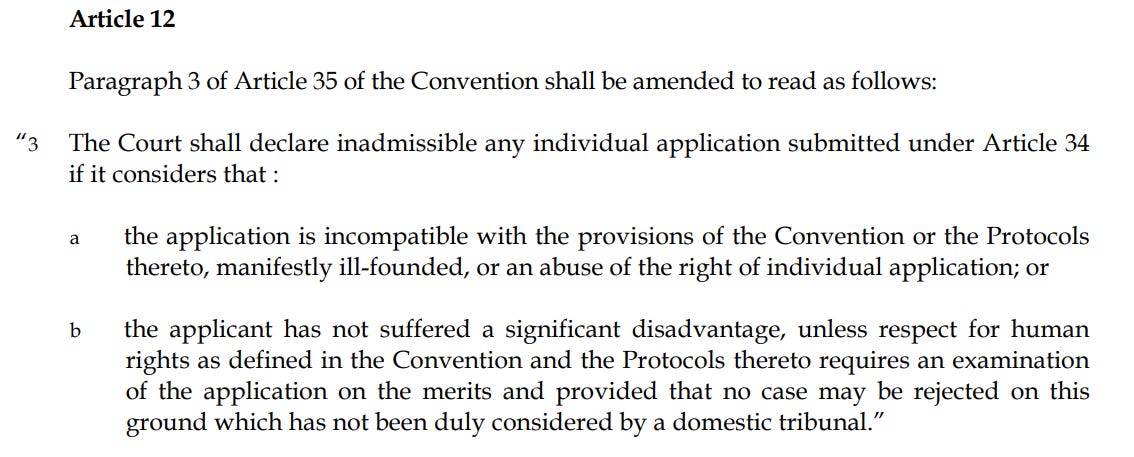

By reason of the success of individual applications to the Court and the backlog thereby created, the Council of Europe passed Protocol 14, to streamline the work of the Court. In Article 12, applications to the Court are limited to applications that can prove that the violation of the Convention by the State constitute a significant disadvantage for the victim.

If the UK repeals the GRA there would be no immediate breach of the Convention. In fact such a concept is absolutely unheard in the context of the Convention. The consequences of repeal are strictly a matter of the domestic law of the UK and there is nothing in the British constitution to fetter the powers of parliament in such a speculative manner, i.e. forbidding the repeal of a law lest there would be a violation of some unspecified right contained in a treaty, albeit a treaty incorporated in UK domestic law, which means its provisions are directly enforceable in UK courts (this is the mechanism by which a country with a dualist system like the UK incorporates international law in its legal system). This brings us to the HRA 1998 and the myths around it.

Repealing the GRA is an immediate violation of the HRA 1998.

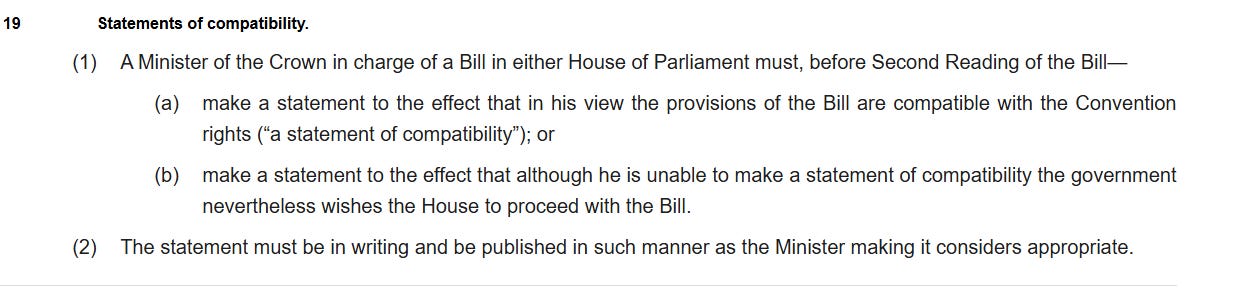

In 1998 the Blair government “brought rights home” by passing the Human Rights Act. By this Act UK nationals were given the right to raise an action against the UK government for violations of the ECHR as incorporated in domestic law through it. The Act had to take into account the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. In the British constitution, parliaments cannot be fettered. How to reconcile this with a UK court hearing cases on the basis of a foreign treaty, albeit incorporated in UK law? The solution found by the HRA is elegant in its simplicity. There are two moments in which UK law takes into account the ECHR. When legislating, a statement of compatibility has to be issued for all new legislative acts by a Minister of the Crown. Note that this is contained in the section of the act dedicated to parliamentary procedure, clarifying that this is a procedural obligation.

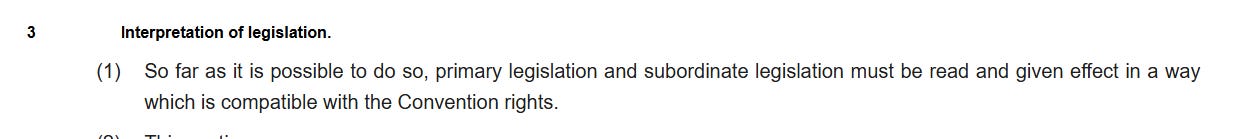

In the context of judicial proceedings, courts are enjoined to interpret, to the extent possible, UK law so as to be compatible with the Convention. This is an iteration of the well known Charming Betsy doctrine (when a case has a funny name like that it concerns a ship). This was a case in the US Supreme Court in 1804 where the Court said that “an act of Congress ought never to be construed to violate the laws of nations if any other possible construction remains.” This canon of statutory interpretation dictates not that the courts have to interpret domestic law so that it is not in conflict with international law but that, faced with more than one interpretation, they ought to choose the one that is consistent with international law. Section 3 of the HRA contains this duty for UK courts:

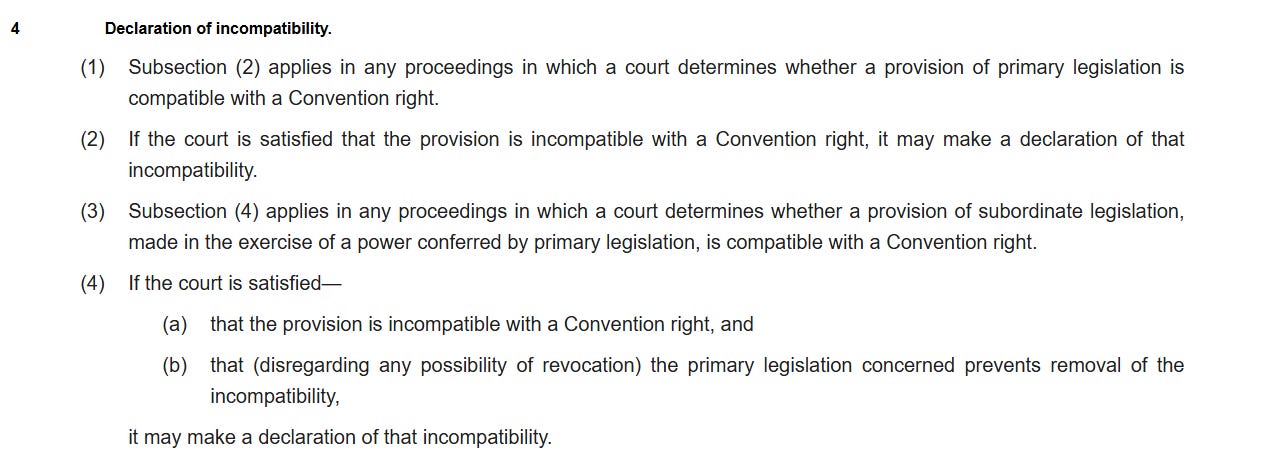

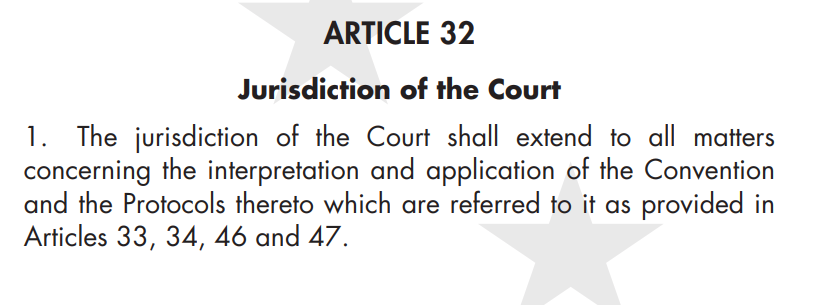

Clearly there is no absolute duty to interpret UK law so that it complies with the Convention. At times UK courts will be faced with laws that cannot be interpreted in such a manner. Section 4 illustrates what courts need to do in that case.

Section 4(6) details what the effects of a declaration of incompatibility are and is very important.

This is the provision whereby parliamentary sovereignty is maintained. The Courts do not have the power to affect the validity of the incompatible law (the US Supreme Court has this power, thanks to the Marbury doctrine). Additionally, their decision is not binding on the parties to the proceedings. The effect of this section is that even a declaration of incompatibility of the Act of repeal of the GRA would not affect the validity of the Act.

A repeal of the GRA will automatically result in a declaration of incompatibility and/or a breach of the ECHR.

There are several things to be said in this regard some of which are not within my area of competence, but even I know that such a sweeping statement is legally illiterate. In the first instance it does not distinguish between a judicial review action and a claim of breach of Convention rights as domesticated in the HRA. It seems more likely that the government would not face a judicial review action. Nonetheless one would need to prove that repealing the GRA directly affected them and constituted a violation of their Convention rights. The content of the GRA would of course be of the utmost importance. Regardless of what has been claimed, the GRA is not an act of constitutional importance protecting a fundamental right to sexual/gender identity. The word identity in that sense does not even appear once in the GRA. It is true that the case law of the ECHR has developed in the last twenty years since Goodwin to incorporate the legally vague and imprecise concept of gender identity into its own case law. But there are two important provisos to this legal developments, one international and one domestic, which reflects the international rule.

Cases of the ECHR are “law”.

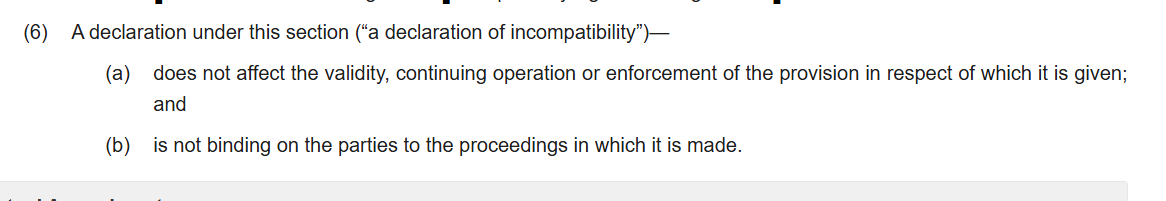

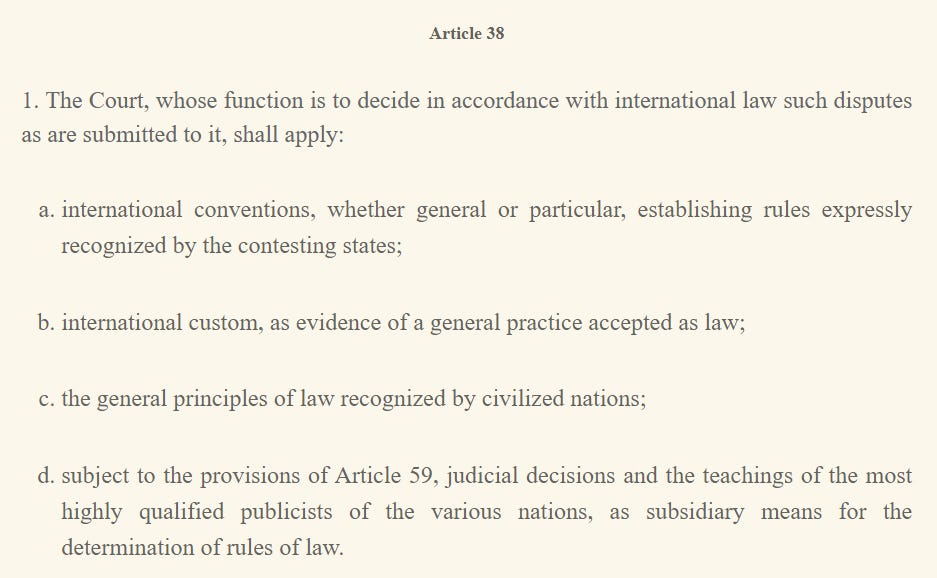

This is one of the most widespread myths, disseminated by legal scholars who really should know better. International law is not a form of domestic law modelled on UK law. There are two important consequences to this difference. The first is that there is no hierarchy in international courts, no “supreme court” and no court capable of binding lower courts. Each court is an entity unto itself, a creature of a treaty and bound by the rules therein contained. The functioning of the ECtHR is dictated by the Convention. The second one is that courts are not bound by their previous case law and can depart from it, though of course they need a reason to do so. This is not a lesson on the ECtHR so I am not going into detail on how and why. Suffice to say that they can “change their mind” and if they had not in Goodwin, reverting almost twenty years of previous case law, I would not be writing this piece. Finally, the only ones bound by the decisions of the court are the parties to the proceedings, which normally means the State party to the proceedings (the Convention provides for inter-State cases, but these are rare). This brings us to the most important conclusion: cases are not law in international law. The so-called sources of law are contained in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. There is no need to consider the difference between what is law and what is the applicable law in the context of international judicial proceedings.

Article 59 states that decisions of the Court are only binding to the parties to the case. But, you may add, what does the Statute of the ICJ have to do with the applicable law in the ECHR? Well, it is considered customary law (see Article 38(b)) so it matters. In any event, the ECHR contains a specific article on the jurisdiction of the court, quite limited to matters arising under the Convention.

As I said, international courts are creatures of treaties and bound by the rules they contain. Previous case law is not law and the court has to consider questions of facts carefully in order to determine whether the individual applicant’s facts preclude them from relying on previous case law to come to a finding of violation of a specific right.

Gender identity is protected under the ECHR and repealing the GRA would force UK courts to rely on the law of the ECHR.

I think by now you can see the misconception. The ECtHR does not make law as we just said. Gender identity is not protected under the Convention and repealing the GRA has not an ipso facto breaching effect. The Convention, written in 1950, does not contain naturally any reference to gender identity, a term that had not even been invented yet. All the cases concerning transsexual/transgender people (the language changed with the times) arise under Article 8, right to private and family life. The closest one comes to the incorporation of gender identity in the text of the Convention is Article 14, the non-discrimination article.

Gender identity can be included in the “other status” category. All the same, normally the Court will not find a free-standing violation of Article 14, but only in relation of another protected right: in the case of transgender individuals, this has been Article 8. There is a lot to be said in the reconceptualisation of the right to privacy, which Justice Brandeis (who invented the concept of privacy) defined as the right to be let alone, so a classic negative right of no interference, into a positive right, whereby the State has to recognise your delusions about your sex. Be that as it may, UK courts do not have to comply with the increasingly deranged jurisprudence of the ECtHR on this matter. The HRA has specific rules on this. Section 2 is titled “interpretation of Convention rights” and it states as follows:

Take into account does not mean apply or comply with (in law every single linguistic choice is important, one of the reasons why the meaningless gender is so infuriating to good lawyers, and I stress the word good). In short, there is no legal duty for UK courts to follow the jurisprudence of the court, especially if doing so would mean, as one could argue, disregarding women’s rights.

Repealing the GRA would force/compel the UK to leave the ECHR/Council of Europe.

Here one word really suffices. Bullshit. No country was ever expelled for a minor procedural infraction (granting a document is at most a procedural breach). Only Russia was expelled for invading Ukraine. Several countries do not have anything approaching the GRA and, ironically, the UK has been criticised for having such outdated legislation as the GRA. The requirement of a diagnosis of gender dysphoria goes against the latest ICD (International Classification of Diseases) by the WHO, ICD-11, which replaced it with gender incongruence and moved it from the section on mental health to the section on sexual health. Whoever claims the Council of Europe prevents the UK from repealing the GRA can thereby be dismissed as incompetent.

International law effectively prevents the UK from repealing the GRA or would force the UK to follow self-ID as the standard.

Here we get to higher level misconceptions and myth, caused by a basic misapprehension of how international law works. Article 38 mentions customary law, as “evidence of a general practice accepted as law”. What does that mean? General practice means an almost universal coherence and consistency in respect to a certain behaviour. But this is not enough. No country offers a dinner of fish fingers when a foreign president makes a state visit. But this is not enough to make it law. The practice has to be “accepted as law”. So countries have to follow the practice because they believe they ought to follow the practice out of legal obligation and not, for example, comity among nations or simply good manners. This is called opinio iuris and is a necessary element in the formation of customary law. What constitutes practice for the purpose of customary law is equally important. Practice refers to State practice, so everything States do and crucially, States say. The judgments of international courts are not practice for the purpose of customary law, but the submissions of States in the proceedings are. Confusingly treaties, the main source of international law, or better, international obligations (at this point I am quite aware only international lawyers are following me) are also an example of practice for the formation of customary law. You may ask why do we need customary rules if we also have treaties covering the same subject matter, and what the difference is. If I was still teaching international law, you would get a whole lecture on why (I loved teaching what I called “the grammar” of international law and structured all my introductory courses around it). But here I want to focus on something else. As I said, what States say is crucial to the formation of customary law. This is why the complaint that international law is just States making statements is so misconceived. Making statement is actually States making, or developing, the law. And when States do not want the law to develop in a particular direction, they ought to express this directly, otherwise their silence could be taken for consensus (what in law is called acquiescence). So to try to gag States from making statements, or passing legislation, that openly contradicts the developing consensus around the idea that gender identity trumps sex or replaces sex, is particularly invidious. Even when a consensus does develop around a new rule, States that consistently object (the so-called persistent objectors) can avoid being bound by the new developing rule. In the Draft Conclusion on Identification of Customary International Law of 2018, the International Law Commission puts it like this:

Basically, States ought to have unfettered freedom to object to emerging rules of customary law, except for what concerns peremptory norms (stuff like genocide and torture). To the extent that a concerted attempt is made to smuggle in gender identity as a form of customary rule (though by no means there is a universal practice as of yet), States ought to be able to object as loudly and clearly as they see fit. I find this attempt to moderate the debate and silence the dissenters who could be making the very arguments States may rely upon to make their position known extremely disturbing. After all, “the most highly qualified publicists” (international lawyers) are, according to Article 38(d) are a subsidiary mean for the interpretation of international law.

OK enough for now.

"Confusingly treaties, the main source of international law, or better, international obligations (at this point I am quite aware only international lawyers are following me) are also an example of practice for the formation of customary law."

Not a lawyer of any description but definitely following you - although I would also definitely fail an exam if asked to explain.

Very helpful article. Thank you!

I support repeal of the GRA and think emphatically everything about the whole "mismatched gender identity" narrative has to go.

I have had a letter published by the medical evidence charity HealthSense that aims to shift the Overton window towards this aim, I include it for your interest:

https://www.healthsense-uk.org/publications/newsletter/newsletter-128/434-128-letter.html